Return to Toolkit homepage

Definition

Oral history is the recording of people’s memories, attitudes, feelings and opinions and enables the listener to have some understanding of that person and their experiences. It can cover their whole life, an aspect of that life, or a particular event significant for them or more generally well known.

What oral history offers

It enables people who might not otherwise be heard to recount aspects of their lives. Potentially everyone has a unique story to share, regardless of colour, race, religion, age, upbringing, career, economic circumstances and life experiences. Oral history may not be entirely accurate as memory is subjective and emotive but these aspects can also be a strength.

Oral history enables us to document details of everyday life and ensure the experiences, opinions and outlook of people in general are recorded. Gaps in historical evidence might be filled and alternative views of events put forward. Alternative, or poorly documented, ways of life could be better understood.

The Instititute of Historical Research has a comprehensive account of how oral history has developed over many years.

Wikipedia has an overview of oral history worldwide; USA dominated but with useful links to many articles and examples of projects.

How to produce worthwhile oral history

A good oral history interview will be conducted by an interviewer who has discussed the interview in general terms with their subject, put together a structured set of questions, can be adaptable and is familiar with their recording equipment. They will also insure that the recording is preserved in a library, record office or museum, and that consent forms for its use are signed. The process can lead to the discovery and donation, or loan for copying, of documents, photographs and other records which can add value to the recorded interview.

A variety of recording devices can be used but heritage staff should use the best digital recorders their budget will allow, ideally with microphones and headphones, and not mobile phones. The latter have limitations, particularly poor quality internal microphones and limited file saving options.

How to create or enlarge an oral history collection

Firstly, be aware that every interview is time-consuming to prepare, conduct, summarise or transcribe, save and catalogue. So your initial decision is: am I planning one-off interviews or a larger scale project involving other colleagues, volunteers and often external funding.

Secondly, why am I planning to create or enlarge an oral history collection? It may be to capture eye witness memories from people who remember life before/during the Second World War, from a particular time period or of living in a particular place. Another reason may be that there are few books or records on a particular event, place, or type of community . Also, are specific outputs (eg exhibition or book) required as part of a wider OH project, in which case including specific questions on particular themes (eg childhood, work, leisure, food etc) may be needed.

Thirdly, can my organisation fund this in-house or do I need to look for external funding for part or all of the cost, and if so, how much.

The Oral History Society has excellent advice on how to get started both on their website and through ideas in their Oral history journal.

Funding a project

The most obvious organisation to approach is the National Lottery Heritage Fund. They welcome projects which are oral history based and have published excellent guidelines on funding, scoping, planning, executing and archiving an oral history project. The Oral History Society has a list of other funders and with links to directories of grant making organisations.

Working out how much funding to ask for is made easier through the Society’s budgeting for oral history contractors pages, covering estimated charges for training sessions, workshops in schools, editing work, etc.

Training

Both staff and volunteers need training in this specialist field whether attempting just a few one-off interviews or a larger project.

The Oral History Society offer a range of training courses in person or online from general courses for beginners through to specific courses on specialist subjects such as archiving, editing and GDPR.

The Institute of Historical Research (University of London) also offers training courses, seminars and other events on understanding, setting up and running oral history projects, including a three day annual oral history Spring School.

Equipment

Various organisations offer advice on choosing and using digital recorders, microphones, headphones etc including the USA’s Institute of Museum and Library Studies, Digital Omnium and the Oral History Society debates the merits of audio versus video too.

Practicalities of interviewing

Excellent advice on the whole interviewing process is available from the Oral History Society including ethical, legal and data protection issues.

Some practical tips:

- Conduct the interview in a quiet place, somewhere your interviewee is comfortable, away from traffic noise and other internal noise [eg loud clocks, budgies etc!] but near a power supply

- Place the recorder on a magazine or towel etc to reduce noise

- Adjust sound levels and record/listen to some test conversation before

- Ensure the interviewee doesn’t have anything which might cause distracting noise, such as sheets of paper, keys, cups etc

- Mobile phones may affect recording even on silent; turn them off

- Explain the purpose of interview, particularly any project background, how the recording will be used and that they’ll need to sign a copyright and clearance form afterwards for it to be used

- Explain the nature of the interview – reassure them that it will be relaxed, informal, their words, and you will guide them

- If a friend or relative is present, ask them to intervene as little as possible during the interview

- Always begin the audio interview by identifying yourselves, the interviewee, and the date, using standard introductory words

- Let them talk! Actively listen to and respect your interviewee

- Use ‘open’ questions to encourage them to speak

- Let them tell their story in their own way

- Use your list of questions – but be flexible, allow the interview conversation to follow other directions to those predicted by your question sheet; also ask other questions if and when they occur to you during the interview

- Don’t interrupt; your voice should be heard as little as possible

- When they have finished answering a particular question, count to 10 before you carry on; they might be thinking and add something significant

- Acknowledge as quietly (ideally silently) as possible what the interviewee is saying; avoid saying ‘ok’ and ‘mmmm’ frequently unless the interviewee is partially sighted

- Above all, relax and enjoy the experience!

Straight after the interview, ask the interviewee to complete and sign a copyright and clearance form. Your interviewer(s) should also sign the same form or an additional copyright and clearance form. Without this the recording should not be added to your collection. Ideally complete two copies, leaving one with your subject.

Take a photograph of the interviewee if they consent and add this fact to the copyright and clearance form. This may be used later if any audio is added to a website. Similarly photograph any significant personal documents and items which might be relevant to, or have been mentioned in, the interview. Add details of these to the same form, or use a separate form (if preferred), for these.

Post interview work

- Save the original .wav (archival) file on a backed up server or in two different physical locations (external hard drives, SD card or similar)

- Make two .mp3 copies of the .wav file(s) which will be the working copies and should also be saved in two different locations (as above)

- The .mp3 file can be edited to remove introductory sound tests etc; Audacity is a free, open source audio editing software; more functions are offered by these paid-for alternatives: Goldwave, Wavelab Elements or Sound Forge Audio Studio 12

- Send a thank you letter with a copy of the interview on CD

- Back up and catalogue the digital master recordings (.wav files), .mp3 copies, timed summary plus copies of all printed documentation (particularly signed agreements)

- Consider depositing the digital master recordings (.wav files), .mp3 copies and printed documentation (particularly signed agreements) at an appropriate local record office too, if you don’t have the capacity for long term preservation

- Produce a detailed summary of the recording, including the person’s details, date/location of interview and subjects covered with timings; make a note of any potentially offensive statements (see ‘Ethics’ below’); NB full text transcripts are very time-consuming to produce

- Ethics: it is important not to change the meaning of the interviewee’s words or use recordings in a way which might embarrass them; don’t publish offensive, libellous or slanderous comments about a third party too; check what permissions the interviewee has given on the copyright and clearance form; see the Oral History Society’s section on ethics

- The copyright and clearance form, and any other signed forms produced, should be filed and ideally digitised

Exploiting Your OH Collections

Short audio clips can be made from much longer interviews, using software described in ‘Post Interview Work’ above. These could be accompanied by a transcript, plus portrait photo, and organised thematically on your website. You can also make simple videos using software such as Movie Maker which enables you to add images to the audio to enhance the clip.

If part of a wider project think about creative responses with schools or in family learning activities, such as animation, or perhaps creative writing. It is worth working with, or employing creative practitioners, so consider including costs for this in any funding bids. [thank you to Terry Bracher for these ideas]

Bibliography

A comprehensive worldwide bibliography is available on the Oral History Society website which includes sections on Handbooks, Collections and Reflections on Theory and Practice, Periodicals and Key Studies Using oral history.

Selective list of books:

A. Bryson and S. McConville, The Routledge Guide to Interviewing: Oral history, Social Enquiry and Investigation, (Routledge, 2014)

N. MacKay et al, Community Oral history Toolkit, (Left Coast Press, 2013)

R. Perks and A. Thomson (eds), The Oral history Reader, (Routledge, 3rd ed. 2016)

D. Ritchie, Doing Oral history, (Oxford University Press, 3rd ed. 2015)

D. Ritchie, (ed), The Oxford Handbook of Oral history, (Oxford University Press, 2011)

P. Thompson, The Voice of the Past: Oral history, (Oxford University Press, 4th ed. 2016)

Periodical:

Oral History (Oral History Society, [UK] vol. 1 no. 1 1969–)

Articles:

Toolkits:

Email West Sussex Record Office for a free copy of their practical, comprehensive oral history guidance notes on how to set up, conduct, summarise and save oral history interviews, including example forms.

Manchester Histories Toolkit 2 Doing Your Oral history Project

Written by Dr Fiona Cosson this downloadable toolkit is a step-by-step guide to doing a successful oral history project. It covers all the key steps in the process of putting together your project, from planning and design, to interview skills, and organising your material and transcription.

Websites

GENERAL / NATIONAL

Oral History Society

The best place to start for advice and information on all aspects of oral history. As well as the many links in sections above, there are also special pages on networkers, consultants and trainers, family history, museums, higher education and academic studies using oral history and UK regions.

Oxford LibGuides: Oral history

Perhaps the most comprehensive overview of oral history resources and projects from across the UK and beyond published by the Bodleian Library.

The British Library has an active campaign to identify and help preserve oral history collections across the UK, however the 2023 cyber-attach has brough many of the following resources down. The Directory of UK Sound Collections, resulted from a BL survey in 2015, and has detailed information on 3,015 collections, from 488 collection holders, containing 1.9 million items. This is the most comprehensive and up-to-date survey of oral history, can be downloaded and includes links to online catalogues and websites.

The BL’s Save Our Sounds programme aims to preserve rare and unique sound recordings in the BL and in other collections through a Lottery funded project Unlocking Our Sound Heritage. Additional aims are to establish a national radio archive and to invest in new technology to enable the BL to receive music in digital formats.

The British Library’s own oral history material is one of the largest collections of oral history and life story interviews in the world and there is a specialist online catalogue.

LISTS of UK LIBRARIES and RECORD OFFICES

All UK record offices, many libraries and some museums hold oral history within their collections:

The National Archives’ comprehensive list of record offices and archive collections

UK Government public library finder

Libraries_in_the_United_Kingdom (Wikipedia)

Library.org searchable lists of UK academic and public libraries

SELECTIVE LOCAL oral history PROJECTS and WEBSITES

Bedfordshire_Womens_Land_Army

Birmingham Library Services

Various oral history projects on migrants from Ireland and Caribbean, and veterans of World War Two

Birmingham LGBT

Several heritage projects to research and archive the lives and experiences of LGBT people

Black Country oral histories

Records of over 300 oral history interviews in collections across Dudley, Sandwell, Walsall and Wolverhampton

Cornish Audio Visual Archive

Exmoor Oral history Archive

Over 200 hours of audio recordings featuring 78 people

Essex Record Office Sound and Video Archive

Lake District Holocaust Project

Poignant story of Jewish child holocaust survivors sent to Ambleside after World War Two

Lancashire Textile Project

A sound and photographic archive now at Lancaster University

Leeds: Historypin Connections

Engaging with older adults at risk of social isolation, both individually and in groups, this partnership project between Leeds Library & Information Service, Norfolk Library & Information Service and Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums is funded by the Big Lottery Accelerating Ideas programme

LONDON

Bishopsgate Institute

The Special Collections and Archives include personal histories and reflections from the 1940’s to the present, in two key areas: everyday lives of Londoners, and grass roots protest and campaigning for social, political and cultural change

Hidden Histories

Oral histories about the wider East End (East Side) of London

Foundling Voices

Memories of separation, schooling, love, loss and rediscovery from people who grew up in the care of the Foundling Hospital between 1912 and 1954

Kings Cross Voices

An unusual oral history project, recording the memories of railway workers, police officers, market traders, activists, former sex trade workers, housewives, artists, students, publicans etc, between 2004 to 2008, before the area was redeveloped

Museum of London Oral history Collections

An overview of the Museum’s oral history collections with extracts from interviewees related to the ‘Windrush Generation’ of Afro-Caribbean migrants

Ports of Call

Walking trails about communities around the Royal Docks, with downloadable maps and oral history mp3 files

On the Record

An unusual collection of oral history projects with a social change agenda, most based in the East End: childhood food, childcare and parenting, a Hackney community centre, specialist hospitals, and Speakers’ Corner

Waltham Forest

Over 800 interviews and 52 sound clips from London’s oldest (1983) oral history group

Manchester

Ahmed Iqbal Ullah Race Relations Resource Centre

Over 200 OH interviews with ethnic minority residents including Afghan, African, Sikh, Bangladeshi, Caribbean, Chinese, , Indian, Kurdish, Pakistani and Somali people.

Milton Keynes All Change

oral history recordings, images and documents on the coming of railway towns Wolverton and New Bradwell

Norfolk: Historypin Connections

Engaging with older adults at risk of social isolation, both individually and in groups, this partnership project between Leeds Library & Information Service, Norfolk Library & Information Service and Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums is funded by the Big Lottery Accelerating Ideas programme

North_West_Sound_Archive

Sound recordings relocated to Manchester Central Library, Liverpool Central Library and Lancashire Archives

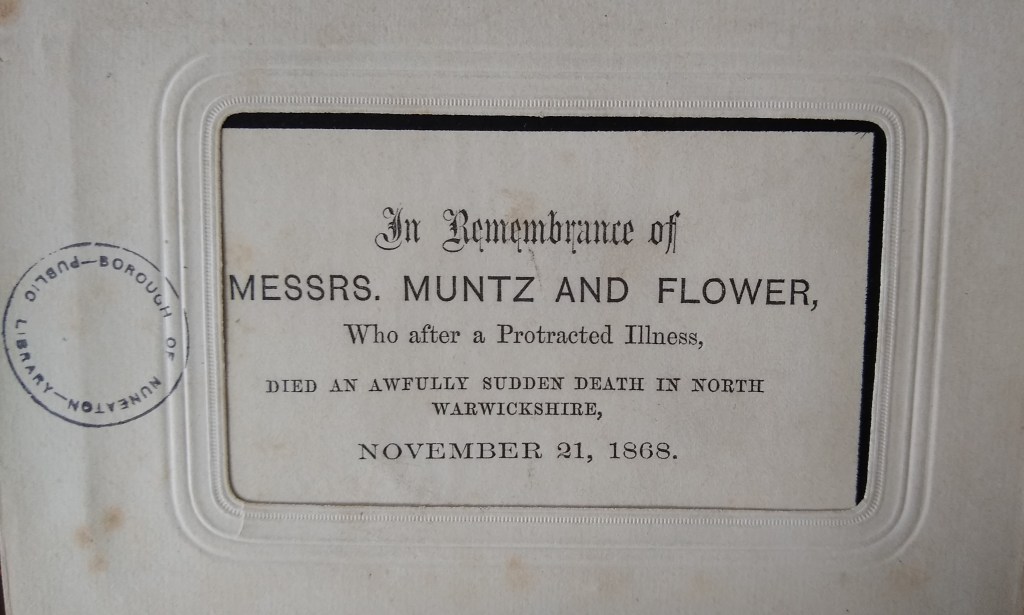

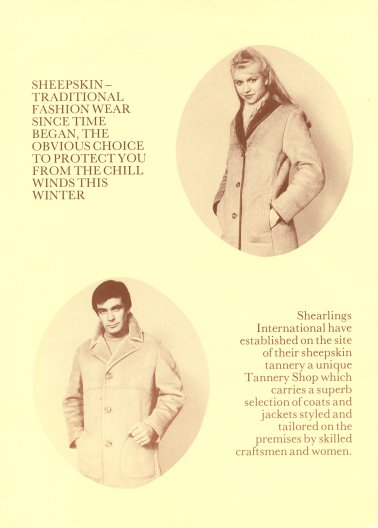

Nuneaton and Bedworth Working Lives

Work and industry in these towns, including audio clips

Reading: The Immigrants Project

Stories of people from all over the world who came to settle in Reading

Southwold Museum and Heritage Society

Example of how to embed audio clips across a local history website

Tyne & Wear: Historypin Connections

Engaging with older adults at risk of social isolation, both individually and in groups, this partnership project between Leeds Library & Information Service, Norfolk Library & Information Service and Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums is funded by the Big Lottery Accelerating Ideas programme

East Sussex Record Office [The Keep]

Keep Sounds is part of the British Library Unlocking Our Sound Heritage and has blogs on the importance of OH, history of recording, and various topics such as the significance of libraries, Ashdown Forest, Brighton’s West Pier and even OH during the 2020 lockdown.

West Sussex CC Library Service

These projects were funded by the National Lottery Heritage Fund:

Military Voices Past and Present

Audio extracts from Interviews with West Sussex veterans from World War One, World War Two and post 1945 wars and conflicts.

Wartime_West_Sussex 1939-45

200 audio clips of 24 people interviewed about their experiences of the Home Front in West Sussex

Wiltshire & Swindon History Centre Projects: The projects below received funding from the National Lottery Heritage Fund:

- Lacock: a Sense of Place – Interviews with local residents added to the online Lacock Community Archive

- Wiltshire Black History – Interviews with people from the local African Caribbean from 2010 to date, based on two projects: SEEME (life stories) and Wiltshire Remembers the Windrush Generation; includes classroom resources

- World War Two Arctic Convoy Project – Oral histories of veterans who served on the Arctic convoys between the UK, North America and Iceland between August 1941 and May 1945

- Do You Remember… Reminiscence Sessions in Wiltshire Care Homes, A Pilot

IRELAND and NORTHERN IRELAND

Oral History Society Northern Ireland Network

Oxford Lib Guide on Oral history in Ireland

Another Oxford Library Guides by the Bodleian

Oral history Network Ireland

SCOTLAND

Living Memory Association, Edinburgh

Reminiscence group established 1986, with interviews, podcasts, videos, and strong on music, photos and a Facebook page

University of Edinburgh School of Scottish Studies Sound Archive

Established in 1951 and contains thousands of recordings of songs, instrumental music, tales, verse, customs, beliefs, place-names, biographical information and local history. Strong on traditional life, farming, fishing, ship-building and other industries described in a range of dialects and accents in Gaelic, Scots and English

Glasgow Life

Various oral history projects across the City:

Scottish Oral history Centre

Established in 1951 at the University of Strathclyde, the Centre supports the use of oral history within the academic community and in the cognate areas such as archives and museums and aims to encourage best practice in oral history

Tobar an Dualchais/Kist o Riches (Gaelic language)

Set up to preserve, digitise, catalogue and make available online Gaelic and Scots recordings and nearly 50,000 are available online.

WALES

Oxford Lib Guide on Oral History in Wales

A guide to collections including Welsh recordings in institutions across the UK

Unlocking Wales’s Oral history Interviews

The National Library of Wales is collaborating with the British Library on the Unlocking Our Sound Heritage project. They are digitising and cataloguing some 5,000 sound recordings from across Wales to protect them for future generations.

St Fagans National Museum of History

Example: Women’s history; includes audio clips in Welsh

Got something to add?

Do you have any comments, suggestions or updates for this page? Add a comment below or contact us. This toolkit is only as good as you make it.

Return to Toolkit homepage