Return to Toolkit homepage

What is a Community Archive?

Community Archives started to grow in the early 2000s and are now a popular form for local communities, local history groups and projects tending to collate and make available information, collections and resources, normally online; creating an archive of material that has often not been deposited with a Local Studies Library or Archive Centre. These archives sometimes become a halfway house, attracting copies of material from individuals, families and local groups who are not yet ready to deposit or donate them to a Local Studies Library or Archive Centre.

The national portal that links to many community archives is organised by the Community Archives and Heritage Group. The Group’s website is also the best source of information on community archives.

There are different types of community archive:

- Collections relating to the history and memory of a local community. For example:

- Collections that have a shared theme or interest, for example:

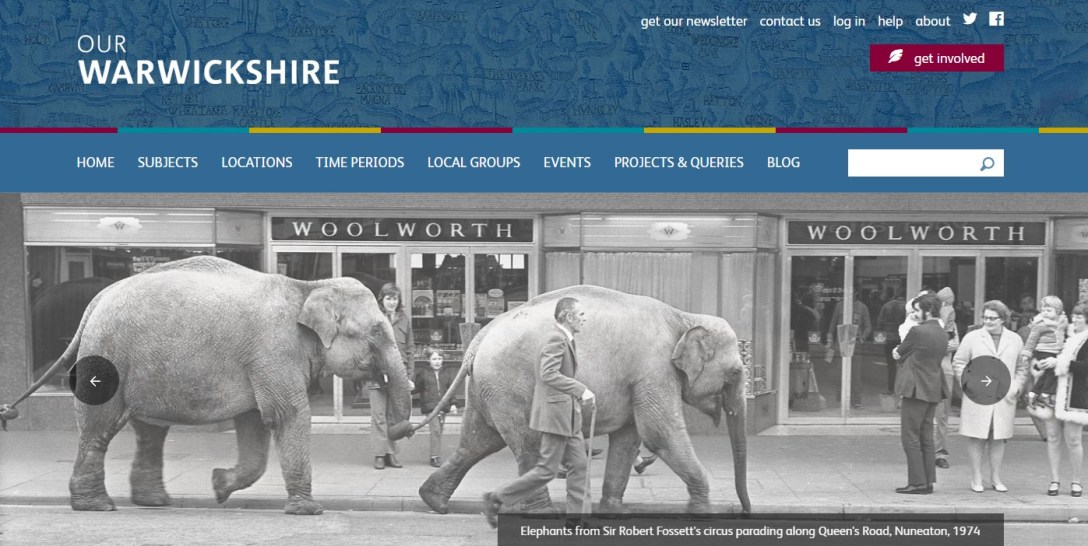

- All-encompassing area-based community online portals that that bring to together a number of smaller collections, allowing each community to upload and share their resources and information.

Information is generally collected through some form of crowd sourcing, and is either collated centrally or uploaded and made accessible digitally by the donor.

There are also physical archives where a Local History Group or community of interest have collected original records, books, photographs and photocopies of material held together in one location that have not been digitised.

Community involvement is key to any community archive and the widest engagement should be encouraged, though inevitably such a project will be driven by a small number of enthusiastic volunteers or local champions collecting, scanning and uploading material.

The role Local studies librarians can play in community archives

Source of information

Local Studies Collections hold a wealth of information that would be of interest to those creating and running community archives, so they are likely to become regular users of your collection and a relationship would build up in the same way as it does with other users.

Advisor

Often the idea and impetus for creating a community archive comes from within the community itself and therefore the role of the Local Studies librarian is to support and encourage; for example providing advice on collecting policies, themes, website structure, metadata, applying for funding; and, if it is a physical archive, collection care and cataloguing.

Technology Provider

The library service or archive may also wish to create a space or a portal for communities to share and upload their digital material. The advantages are that it becomes a standard format and provides consistency and editing. However, it is less required nowadays with relatively cheap websites, the availability of grant funding to local heritage projects, notably through lottery bids, the increasingly powerful search engines and an increase in the number of volunteers with technological know-how which have all have encouraged local communities to set up their own digital archive.

Community space

Libraries, especially local community branch libraries, can provide spaces for community collecting activities and events.

Local co-ordinator

Is there potential to provide some form of hub that links to all the community archives in your area or to create community forums and networks to share knowledge and information?

Long-term home

As with any group, community archives can run out of steam. If that happens material may be deposited with the Local Studies Collection.

Creating a community archive

You will find significant help on the Community Archives and Heritage Group website and Norwich Archive’s website. But some basic things to consider are:

Develop your own website and database or buy off the shelf?

Costs of software can be important in any decision to create a community archive. Open source websites such as Joomla and WordPress are not always free as they require regular updates to guard against hacking etc., while some versions will cease to be supported. It will generally require some time from a professional developer. There are commercial packages available, sometimes developed by other community archives. These have the benefit of providing a structure that works and ongoing support.

If the archive is a physical collection….

How is it being stored? Does it contain original or duplicate material? is it catalogued and is the catalogue digital? How is the collection accessed?

Collecting

It is important to develop a collecting policy. What materials are you requesting e.g. photographs, ephemera, letters, extracts from diaries, oral histories? Are you asking people to supply text and written histories? Are you collecting around specific subject areas? Are there any cut-off dates or other constraints?

How are you going to collect material?

Are you requiring members of the public to upload material and information? Or will you organise a group of volunteers or champions who know the community and are trusted by them. How will you publicise this?

Copyright, reproduction rights, data protection and future use

Does the contributor hold the rights to reproduce the item? Does it include personal data that may not be shared? If it can be shared there is a requirement to be clear with contributors how their material will be accessed and used and for them to agree terms and conditions when uploading or sharing material or information. This can be a delicate balance when you are trying to encourage people to share.

Metadata/cataloguing

The usual rules should apply in terms of ensuring metadata is recorded and there are standard fields and consistency. Considerations should also be given to the use a subject thesaurus and a standard gazetteer of place names. If the community is retaining a hardcopy archive it also worth exploring if the amount of material involved requires the implementation of a catalogue as opposed to a simple list of items.

Formats and digital preservation

It is important to agree file types and sizes. For example, if you are including sound clips a WAV file will be a very large high quality uncompressed file with no data loss and generally used for archiving, rather than MP3 / MP4 that tend to be compressed smaller files and better for sharing but have some data loss with poorer sound quality. If photographs and other image files are to be uploaded, what format do you want them in e.g. RAW, TIF or JPG, and will they automatically be resized for a website when uploaded or will the person supplying the image need to do this before they share it? What actions are you taking to ensure the digital files can be preserved for the future, will it be possible to archive or access formats and databases in the future? Are copies of the text and image files kept separately for deployment in the future?

Long term funding

If you receive project funding it is also worth considering how you will maintain funding and maintenance of a website and a database once the project and grant funding is finished.

Ethics of editing

If contributors are providing text such as a history of a place or buildings, a biography or family history, you will need to decide how much editing you will undertake and who is undertaking the moderating. Often, like oral history, they include people’s memories that may differ from the previous known facts. It is useful to create an editorial policy i.e. are you simply correcting spelling, standardising place names, correcting known errors in dates etc.

Overcoming the challenge of collecting material for the archive

Crowd sourcing of community archives can be rewarding, providing a good range of material and a great way to include a wider audience. However, there have been examples of projects where it has been difficult to encourage people to take the time to engage with a project and upload material or memories. There are several ways to overcome some of the barriers to collecting:

- It has sometimes required the Local Studies Librarian or a paid project officer to work out in the field building contacts and confidence, collecting and collating information from the community. This tends to increase community engagement.

- Training and support for community champions who take on the role of advocacy for the community archive is needed; they will help collect, collate and upload material. Often community archives are generated and led by a Local History Group and this will sometimes provide a foundation and enthusiastic volunteers for community engagement.

- It is important to find ways to overcome issues such as digital exclusion. Confidence to use IT or being able to afford IT kit in the home can be a barrier for some people to share their photos and memories. Again, it is worth considering a paid officer or community champions to assist, or perhaps provide access and support in local libraries.

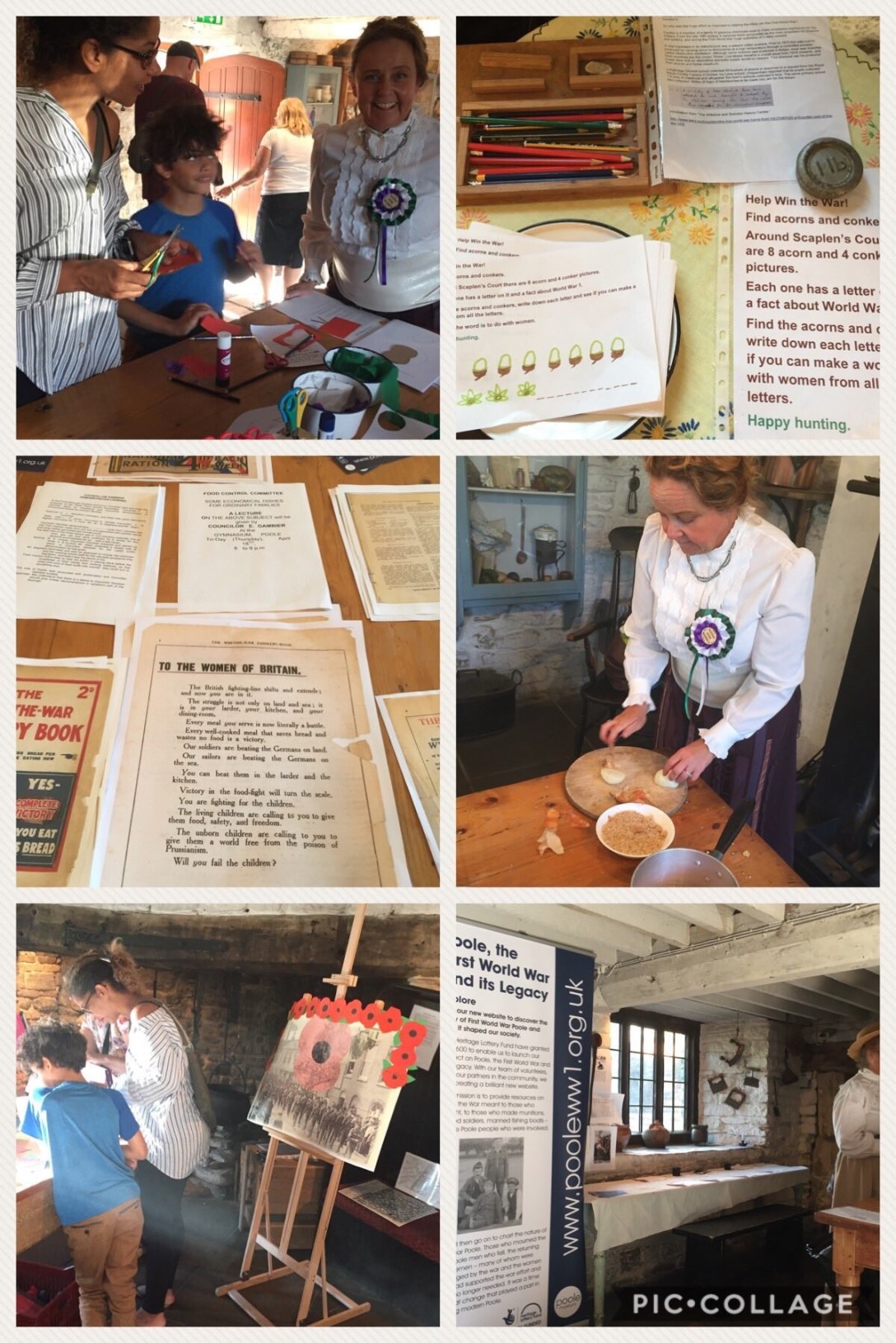

- Another way to encourage sharing is through community activities, such as show and tell sessions, where people are encouraged to bring material along and talk about them.

Further Reading

Got something to add?

Do you have any comments, suggestions or updates for this page? Add a comment below or contact us. This toolkit is only as good as you make it.

Return to Toolkit homepage

Theme image reproduced from the “Our Warwickshire” website under Creative Commons Licence CC BY NC