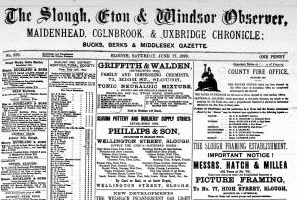

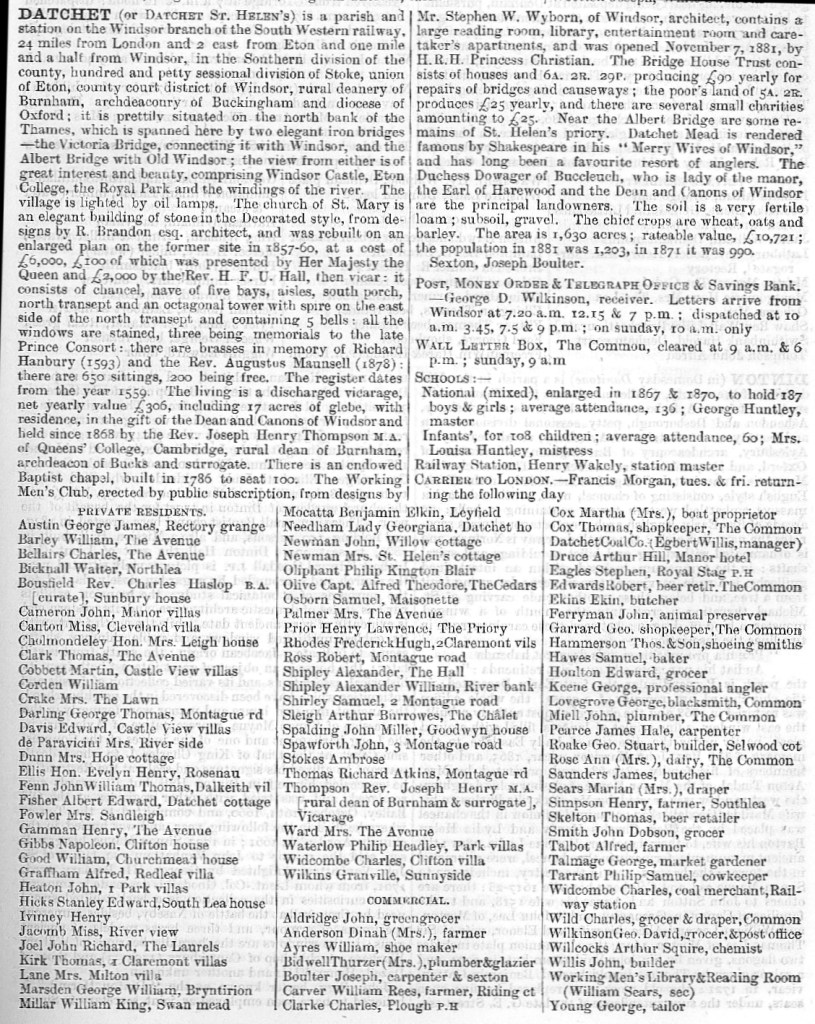

The local newspaper is one of the most useful resources for the capture and later research into the history of a locality. Almost every sizeable town in Britain has (or has had) a local paper, but regrettably the number of printed titles has dwindled in recent years. Some are now only available online.

Many local papers began publication in the mid -19th century at a time when print media was the way that most people received their news. In many instances, the newspaper will be the only place where information on a specific matter has been recorded.

Whilst each paper has its own character, they all contain the same elements; notices, articles and features:

- National and international news in brief

- Regional and local news

- Local government and politics

- Business

- Education

- Social welfare

- Churches and clubs

- Crime and court proceedings

- Obituaries

- Local events

- Sport

- Letters

- Advertisements

- Vacancies and jobs

In the early twentieth century the inclusion of photographs became more widespread, however many titles such as the Illustrated London News had already been using images to enhance features for several decades.

Indexing & newspaper cuttings

Local studies libraries have traditionally created indexes of articles to facilitate the use of newspapers and to increase their usefulness. These are invaluable resources, often giving valuable leads to complex enquiries. Such hard-copy general and obituary indexes to newspapers as well as cuttings should always be maintained. Adding to these indexes is time-consuming but is to be encouraged where staffing permits.

But be warned: other local government officers often do not understand what we are doing and why. In the wake of GDPR legislation some administrators have become over-anxious about online indexes. At the time of writing the online index to newspaper articles compiled by Medway Archives Centre has been removed by order of Medway Council’s GDPR compliance team.

Some authorities have made their newspaper indexes available online:

- Hertfordshire have added their card indexes onto Hertfordshire Names Online

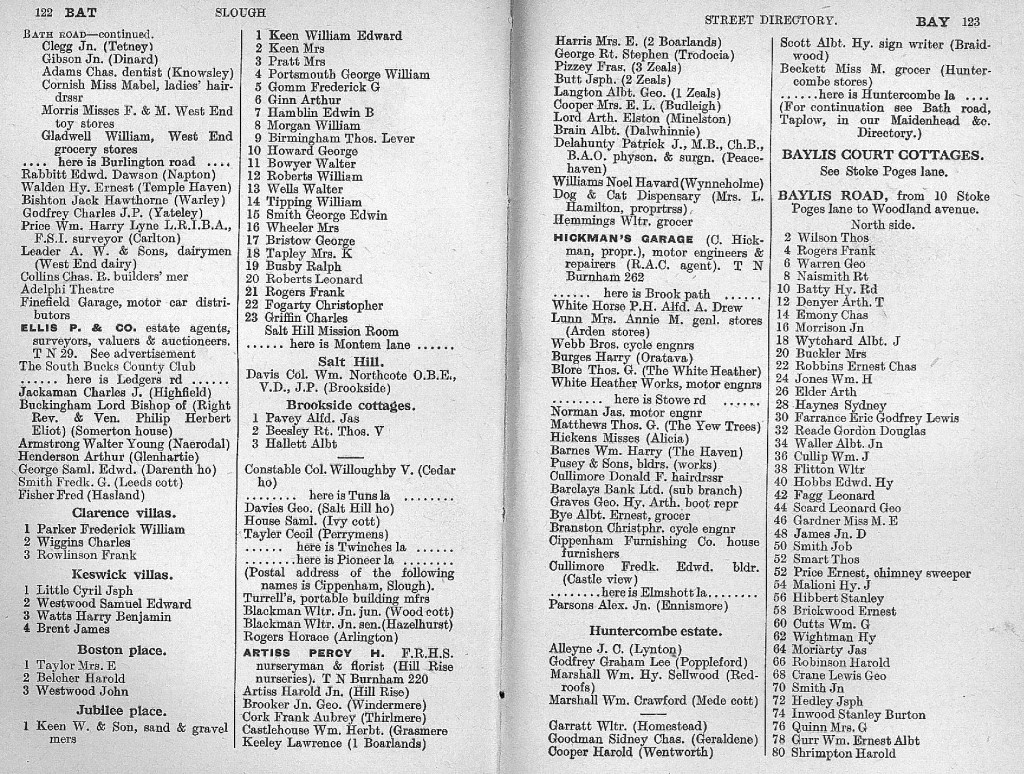

- Slough asked volunteers to index the digitised versions of the Slough Observer on Slough History Online.

Preservation and availability to the user

Newspapers were not printed to last, rather to be read at the time of production. Newsprint paper is often of poor quality, highly acidic and likely to become brittle with handling; so some method of producing surrogates should be used. Surrogates are then made available for public consultation. It is recommended that newspapers should be repaired by professional conservators as often the pages will need to be fully covered by a thin layer of Japanese paper, though small repairs can be done in-house.

Microfilming has until recently been the preferred method of copying as it is a well-established and long-lasting solution. A number of suppliers will produce a master negative and a copy positive. The positive is used by libraries and a new copy is produced from the negative when required. The negative can be stored at another location for increased security.

Digitisation offers an excellent alternative. An advantage of the digital option is that it can include OCR (Optical character recognition). This form of indexing/searching is especially useful, but will of course increase the cost of the surrogate copy. However, OCR can be rather hit and miss for older typefaces, as software finds older typefaces hard to read. Some local newspapers may also supply you with electronic versions of their older newspapers, saving you the time, money and effort digitising paper versions.

Some recent editions of local newspapers are also available via newspaper e-resources. See below for more information. For more information on the discussion on whether to microfilm or scan, read this blog post. Whichever method is used the library needs to have suitable equipment for reading and printing copies for users.

Wherever possible original copies of newspapers should be retained, both as a security measure and to enable images and high-quality text to be reproduced.

Traditionally newspapers have been bound to aid use, but they can also be kept flat in acid-free buffered boxboard boxes.

British Newspaper Archive & other online services

The British Library, until November 2013, offered access to nationwide newspapers at its Colindale site, but this option no longer exists. Original newspapers were moved to a purpose-built storage facility at Boston Spa and free access to papers, both microfilm or original hard copy, is available at the British Library’s St. Pancras site. For more information, read the British Library Newspaper Guide.

The BL has entered into a partnership with the subscription site FindmyPast which hosts the British Newspaper Archive, giving online access to newspapers and journals. The number of available titles is growing all the time, currently boasting over 37 million pages online dating from the 1700s to the present.

It would be fair to say however that coverage of the UK is somewhat patchy; some areas are much better served than others, and for the titles included there may be only a few editions. More recent decades are also less well represented due to copyright issues, with the bulk of their online collections having been published over a hundred years ago.

To view available titles go to https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/home/NewspaperTitles

Many libraries already have access to FindmyPast. For further information on usage in libraries and education go to https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/content/libraries_education

Libraries can also subscribe to local newspaper content, both recent and more historic, via a number of other products:

- Gale provides British Library Newspapers Online through academic libraries and some library authorities. Visit https://www.gale.com/intl/primary-sources/british-library-newspapers for more information.

- Pressreader – includes full digital versions of newspapers such as the Slough Express. For more information, visit https://about.pressreader.com/libraries-institutions/

- Newsbank includes articles from titles such as the Richmond & Twickenham Times.

Other websites offering access to local papers:

- Chronicling America – Historic American newspapers from 1836-1922, sponsored jointly by the National Endowment for the Humanities and Library of Congress (free)

- Gale News Vault – A broad selection of international newspapers and periodicals (paywall)

- Google News Archive – Google’s discontinued newspaper scanning project, whose content is still available to search (free)

- Ireland Old News – Transcriptions of old Irish news articles (free)

- Newspapers.com – Database of 3,400 newspapers, mainly American (paywall)

- Trove – The National Library of Australia’s digitised newspaper collection (free)

- UKpressonline (paywall)

- Welsh Newspapers Online – Welsh and English-language newspapers from 1804-1919, digitised by the National Library of Wales (free).

Further reading:

Got something to add?

Do you have any comments, suggestions or updates for this page? Add a comment below or contact us. This toolkit is only as good as you make it.